Years Active

c. 1600’s

Stage Name(s)

Mary Frith, Moll Cutpurse, Mal Cutpurse

Category

Male Impersonator, Cross-Dresser

Country of Origin

England

Birth – Death

c.1584 – July 26, 1659

Bio

Mary Frith—better known as Moll Cutpurse—was one of early modern London’s most audacious performers: a lifelong wearer of masculine dress, a public entertainer, a notorious thief-entrepreneur, and the living inspiration for one of the Jacobean stage’s most famous plays. During the seventeenth century, the term “roaring boy” in English slang referred to a young man known for public revelry, brawling, and minor criminality. The term was later adapted to describe Mary Frith, whose persistent cross-dressing, public performances, and transgressive behavior made her one of the most notorious figures in early modern London. Frith forged a public identity that fused gender nonconformity, criminal notoriety, and theatrical spectacle. She sang, danced, smoked, fenced stolen goods, disrupted courtrooms, and—most radically—appeared on the professional stage at a time when women were legally banned from performing. Four centuries later, The Roaring Girl, the play written about her while still alive, continues to be staged, confirming Frith’s lasting impact on performance history and gender politics.

From childhood, Mary consistently wore masculine clothing—boots, doublets, cloaks, and later a sword—refusing the restrictive garments expected of women. This was not a disguise or temporary masquerade; Frith’s masculinity was sustained, public, and defiant. Her clothing alone brought repeated legal scrutiny under England’s sumptuary laws(1), which policed gender and class through dress. By age fifteen (c.1599), Frith had her first documented encounter with the law. Over the following decades, she became notorious for riotous behavior: heavy drinking, smoking tobacco, swearing, and frequenting taverns where she would entertain the guests with song and dance. She also ran a business retrieving and fencing stolen property, positioning herself as both criminal and entrepreneur. Pamphlets, ballads, and later biographies circulated widely during her lifetime, embellishing her exploits to address contemporary anxieties about disorderly women and masculine authority.

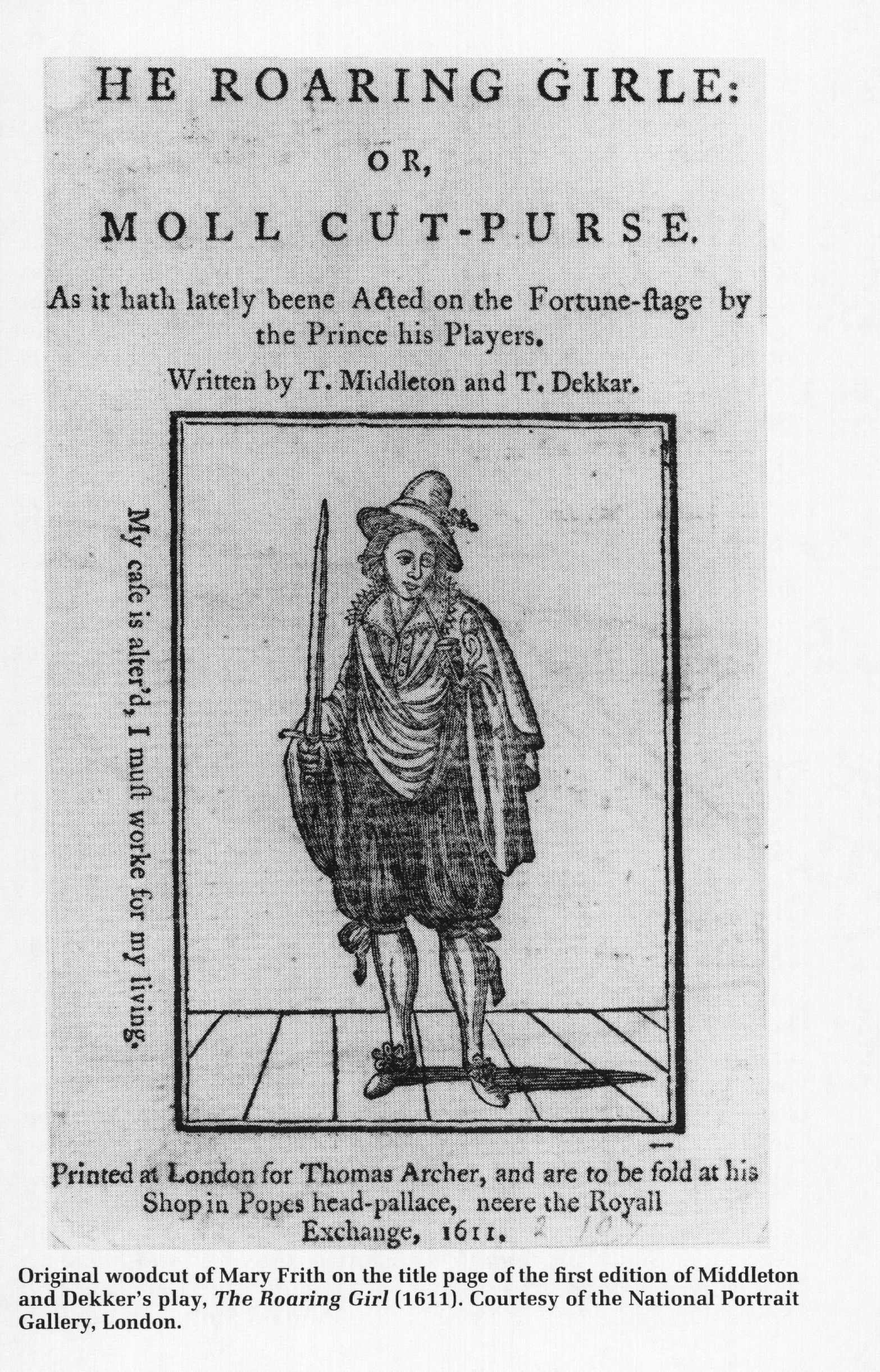

Frith’s reputation reached the stage early. In 1607, playwrights Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker created The Roaring Girl in London, dramatizing her life while she was still alive. The play was published in 1611, cementing her status as a cultural phenomenon. In the drama, Moll Cutpurse openly breaks social rules yet sharply condemns sexually predatory men, positioning her as a moral agent rather than a cautionary figure. Most remarkably, Frith appeared in person at the end of an early performance of The Roaring Girl—likely around 1611—singing, dancing a jig, and playing the lute. This act directly violated the law banning women from the public stage and likely made her the first English woman to perform professionally in a commercial theater. The theatrical layering was extraordinary: while in performance, a male actor would be portraying a woman who cross-dresses as a man is interrupted by the real person herself. A later edition of the play included a frontispiece depicting Moll Cutpurse, often read as an imaginative reconstruction of this moment.

After a 1611 performance at the Fortune Theatre, Frith was summoned to court and forced to confess to wearing men’s clothing and seating herself openly onstage. On another occasion, she was compelled to perform public penance at St. Paul’s Cathedral on Christmas night, and ordered to wear women’s dress. Even then, she resisted, reportedly hiking up her petticoat “in the fashion of a man” and pairing it with a man’s cloak.

Mary Frith died on July 26,1659, one year before the Restoration ushered women onto the English stage in breeches roles. Yet she was already there—performing herself.

Today, The Roaring Girl continues to be staged, often through feminist and queer frameworks that foreground Frith’s lifelong masculinity. Her legacy endures as one of Western theatre’s earliest—and most uncompromising—examples of gender-nonconforming performance.

(Submitted by: Tinamarie Ivey, Dallas, TX)